Adapted from Chapter 1 of the book “Law of Love & The Mathematics of Spirituality”

This book approaches spirituality using mathematical methods similar to those which one will find in science to explain the material world. The credibility of this approach can be questioned if spirituality is viewed as irrevocably wedded to religions which are faith based and not altogether scientific. Association of spirituality with religion is however a historical fact and raises many important questions about the true nature of spirituality: Is spirituality based on faith or can it, like science, be “evidence-based”? Should spirituality necessarily remain distinct from science or do the two have anything in common? Is spiritual progress possible only by the faithful performance of vaguely understood religious rituals or is there a more substantive, objective basis to it? Is its validity totally dependent on the legends and personalities sacred to religions? Do religions have exclusive ownership rights to spirituality or is it conceivable that science one day may also contribute to its advancement? Can the benefits of spirituality be actually experienced in this life by all who practice it, or, is the reward some unnamed heaven to be experienced by a chosen few after their death only?

In short, can spirituality be intelligently pursued, rationally understood and actually experienced here and now? Vedānta, the philosophical system on which much of this book is based, says “Yes”. Spiritual and material realms are part of the one and the same creation. As such, logically speaking, science and spirituality cannot stand in opposition. We will explore in this chapter the mutual relationship between science, spirituality, and religion and show how each can contribute to the welfare of individuals and society without running afoul of one another. The present chapter will also serve as a brief introduction to Vedānta before we get into a more detailed discussion of this philosophy in the subsequent chapters.

Science vs. Religion

Much has been said and written about the constrained relationship between our scientific and religious institutions. Both are great, vital institutions that have served mankind well, though it is not difficult to find numerous instances where both have also been a source of suffering. Science has been generally a constructive force bringing with it many blessings to the modern man. But it has also been misused quite frequently as a destructive power. Similarly, there is no doubt that the great religions of the world have succeeded in providing peace and comfort to their faithful followers from the stress and strain of worldly life; but they have also been misused to incite intense animosities between groups of people resulting in much suffering. These are well documented facts of history.

Well documented too are the many instances where science and religion have clashed. No doubt, both science and religion seek to be on the side of truth. Confrontation occurs when what religion holds as true is not acceptable to science, or vice versa. The approach taken by science to seek and assert truth is quite different from that used by religions. Science accepts as truth only that which can be verified by any observer at anytime by appropriate objective observations. Consistent with this view, science generally preoccupies itself with questions that can be verified through human observation. Religions, on the other hand, deal with many questions which, by their very nature, are beyond the capability of direct observation. They rely on scriptural authority to assert their views on these questions. To the extent the issues of respective interest to science and religion are not overlapping, confrontation between the two can be avoided.

There is some overlap, however, and clashes do occur. For example, religions do have views on origin of the universe and the genesis of human beings which also happen to be areas of great interest to modern science. Here the traditional religious views tend to be at odds with the results of scientific observations. Similarly, some personal and social customs mandated by religions (dietary restrictions, for example) may be contraindicated by scientific principles. Religious dogmatism is often blamed by scientists for the continuation of the controversy in the face of what they consider as objective evidence. But science itself has been blamed as being dogmatic for its view that basic questions of concern to religion, such as God or life after death, are not worthy of discussion since anything we say regarding these cannot be verified by direct observation.

One may rightly despair whether this stand-off between Science and Religion can ever get resolved. A resolution is possible provided we have a right understanding of science and religion and of the mediating role of spirituality. Vedānta, this author believes, provides us with this necessary understanding [3].

What is Vedānta?

Vedānta is a highly developed system of philosophy that finds its first expressions in the scriptures of ancient India known asUpaniṣads. This philosophy has been further developed in other scriptures such as Bhagavad Gītā and Brahma sūtra and interpreted in the elaborate commentaries of generations of subsequent philosophers. Vedānta contains the highest truths in spirituality; many consider it as the science of spirituality because of the rigorous logic employed in analyzing and discriminating truth. It is a science also because of its emphasis on suggesting practical techniques for spiritual development whose promised goals can be personally experienced by the practitioners in their present life. This after all is what a good science is supposed to be- its theories logically sound and predictions personally verifiable.

It is no accident then that the teachings of Vedānta strike a responsive chord in the hearts of many who study it with sincerity. For centuries, great philosophers and scientists around the world have found in it a source of profound wisdom and inspiration. At the same time the real life examples of modern day sages such as Sri Ramana, Nisargadatta Maharaj and Sri Ramakrishna demonstrate the glorious perfection to which any human being can aspire by practicing its teachings. When the German philosopher Schopenhauer exclaims “In the whole world there is no religion or philosophy so sublime and elevating as Vedānta… this Vedānta has been the solace of my life; it will be the solace of my death” it has to be the result of understanding the logic of this science as well as personally experiencing its benefits. Erwin Schrödinger, whose mathematical formulations laid the foundations for Quantum Mechanics, found in the Vedāntic identity of Brahman (bra-hma-n) and Ātman (A-tma-n) “the quintessence of deepest insight into the happenings of the world” [4]. Coming from a scientist with a keen understanding of the behavior of matter and energy in their most subtle form, this comment is indeed a powerful endorsement of Vedānta.

Vedāntic View of Spirituality

The terms spirit and matter are widely used in Western philosophies. The two terms can be best understood by the “seer- seen distinction” central to Vedānta: spirit is concerned with the “seer” whereas matter is everything “seen”. The seer itself cannot be seen, asserts Vedānta. The spiritual life of an individual is then something distinct from its worldly life. The worldly life of an individual consists of transactions at the physical level performed with the aid of its sense organs and organs of action, as well as reactions at the mental level, such as thoughts and emotions. The goal of these worldly transactions is to sustain own life, ensure survival of the species, and more generally to satisfy the emotional and physical needs through appropriate interaction with the world outside. The individual finds worldly happiness to the extent it can satisfy these needs.

The spiritual life of a jīva, on the other hand, has the primary goal of knowing the truth about own self, the world, and the Ultimate Reality (Brahman) underlying both the self and the world. It is not enough to know the truth, but one must live that truth by transforming one’s life accordingly. Spiritual progress demands changing one’s relationship to oneself, to the world around, and to God. The individual realizes peace to the extent it has correct knowledge, and lives established in that knowledge steadfastly.

The happiness in worldly life is obtained through finite actions which can produce only finite results. Therefore worldly happiness is never permanent or complete (i.e. never without some sort of limitation). In contrast, the peace sought after in spiritual life is obtained through knowledge, and not action, and is both total and permanent. It is in this sense that spiritual life is said to lead to Perfection, or salvation, from the limitations of worldly existence. Vedānta teaches the knowledge of own self, the world, and Brahman for our understanding at the intellectual level, and it also prescribes the various practical means by which to realize or live this knowledge so as to attain the promised peace. We need not dwell on this further here since the subsequent chapters of the book are meant to do just that.

Spirituality vs. Religion

Spirituality does not conflict with religion; on the other hand, as mentioned earlier, it is often considered inseparable from religion. This does not mean that the two are the same. For a religion to be effective, it must recognize certain core spiritual truths. This is because the spiritual nature and spiritual development are same in all human beings regardless of time, space, gender, race, nationality etc. Therefore, the various religions that have come into vogue at different epochs in different cultures, even though looking very different, necessarily incorporate many similar, if not identical, basic beliefs about spirituality. Thus, all major religions

1) Place emphasis on controlling the tumultuous mind and living a disciplined, virtuous life,

2) Believe in the existence of a higher power whose Will dictates the events of the world and experiences of the individuals,

3) Preach love and self-less service and require surrender of personal will to the higher Will,

4) Discount the importance of the perishable body in deference to the imperishable indwelling “soul” within each individual,

5) Hold that spiritual practices bring peace and happiness to daily life, and

6) Recognize the potential of all souls to reach Perfection, though some religions suggest that this potential is realized only by own believers.

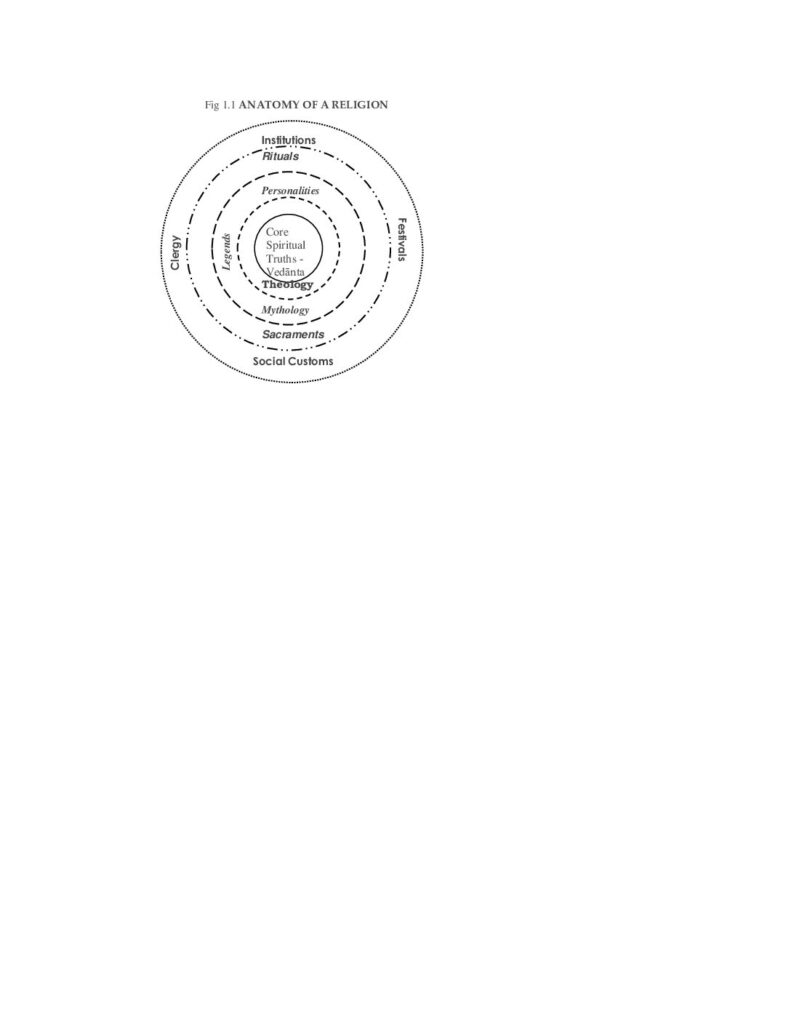

But religions do not stop with just acknowledging and promoting these spiritual truths. They have found it necessary and useful to surround the core truths with several layers of additional theories and practices. The relevance of these additional layers is not universal since they are the product of the particular time, space, and culture in which they are created. As such they do not have the same absolute validity that the core spiritual truths do.

The anatomy of a religion can be visualized as rings surrounding the central core of spiritual truths (Fig 1.1)

The outmost ring consists of the institutions, the temples and churches, the clergy officiating in various positions, the social customs, dress and dietary habits, religious festivals etc. This is the external face the religion presents to the world. The next layer inside represents the various rituals and sacraments that the followers are expected to observe. Usually, this facet of a religion is not open to everyone, but only to its adherents. The third layer is perhaps the most significant of all. It includes the legends and mythologies associated with the various prophets, saints, and deities of the religion. The personalities, ideals and beliefs introduced in this layer often are the factors determining the character of the religion. The next inner layer immediately surrounding the core is Theology dealing with beliefs regarding God, origin of the world, soul, death, life after death etc. Typically, theology involves abstract concepts and theories which the average follower may not totally relate to, but is expected to accept on faith. Vedānta has been identified in Fig 1.1 with the central core because it is the core spiritual truths that are of primary concern to Vedānta. Paul Hourihan put it very effectively when he said “Vedānta is the essence of religion, the truth embedded in the heart of every religion. Vedānta is the Godhead that makes every religion Divine” [5]. This Vedānta, as taught in the Upaniṣads and lived by the Hindu sages, is remarkably simple, honest, and devoid of any worldly embellishments. It recognizes no institutions, no rituals, and stipulates no personality other than own Self as absolutely necessary for salvation[1].

As mentioned earlier, the outer layers that distinguish one religion from others are very much the product of the cultural milieu in which that religion was founded. But the spiritual truths at the core of every religion are invariant over time and space and have no cultural or historic connotations. In this respect they are similar to scientific truths which also must be invariant over time, space and culture.

Much of the difficulty science has with religions has to do with the theology, mythology, personalities and rituals found in the outer layers and less so with the core spiritual truths. We will soon return to discuss this important point at length later.

Religion vs. Religion

Conflict among religions is an unfortunate fact of history, a fact that has repeated itself far too many times. What is the source of this conflict? At some risk of over simplification, we may say it is just “competition”.

Religions do subscribe to essentially the same core truths but frame them in the context of the theology, personalities, institutions, etc that set them apart from other competing religions. In this process, the universal nature of the core truths is often significantly de-emphasized. What is common and unifying is sacrificed in the interest of promoting the brand image of own religion. Some religions are more aggressive than others in pursuing this competitive path.

In this respect, religions may be likened to competing pharmaceutical companies packaging the same generic drug but using different formulations and delivery systems. The formulation can include several ingredients other than the key active agent. The method of delivering the drug could also differ: it could be administered orally, intra-muscularly, by a patch worn on the skin etc. The basic efficacy of the treatment depends, of course, on the pharmacology of the drug and not on its packaging. But when marketing their product, the companies would like to emphasize the benefits of their superior formulation. This is done in order to maximize their market share. No doubt each formulation and delivery method often has its individual advantages and disadvantages in terms of side effects, cost etc. A patient may therefore have a good reason to prefer one brand over others. But it is also true that no single formulation can be considered the best for all patients. A similar situation prevails in the religious scene. One religion does not answer the spiritual needs of all human beings. The true genius of Hinduism lies in recognizing this very important fact. Hinduism respects all religions as potentially equally efficient. But more importantly, it itself offers not one, but a wide range of options for its believers to choose from, all paths having the Vedāntic wisdom as the basis.

There can be no denial of the comfort and support religion provides in one’s day to day life. It is something to which many believers in every religion can bear testimony based on direct personal experience. Social scientists and psychologists also agree on the succor religion provides in facing the problems of life. The positive effect of religion and spirituality on health, and on ability to cope with life, has been documented in scientific studies in recent years [6,7]. However, as far as this author knows, there has been no “head-to-head” unbiased, scientific study in the literature whose results could support a claim of uniform superior efficacy of any one religion over another. As long as the “key active ingredient” in all major religions is the same set of spiritual truths, such evidence is not likely to emerge from future studies either. The conclusion to be drawn here is that the scientifically demonstrable successes of religion are attributable to their common spiritual content and not to the differences in packaging.

Science vs. Spirituality

It can be surmised from what has been said so far that science should have fewer problems with spirituality than with religion. A good deal of spirituality is concerned with practices to ensure happiness here and now in this world rather than in some distant heaven after death. Yoga and meditation, to name two of these practices, have gained acceptance by scientists as having demonstrable salutary benefits on the physical and mental well being of the practitioners. Of the six core spiritual truths listed earlier, the first, third, and fifth have to do with our mental or “inner” life. Scientists do not refute the existence of mind or the importance of inner happiness, even if they do not have a consensus among themselves as to what mind really is. As such, they will not have much to dispute with these three points.

The second, fourth, and sixth points in the list of core truths do refer to concepts of “higher Will” and “imperishable soul” which are not observable entities. Scientists can raise objections as to their validity but close examination will show that these objections themselves are not totally scientific. Thus, we note that modern science has come to accept uncertainty as an inescapable and insurmountable feature of the universe, affecting the very fundamental particles of which matter and energy are constituted. Uncertainty is also inherent in human decisions and affects our daily lives even more directly and profoundly. It can be argued that acknowledging this basic uncertainty is tantamount to postulating a higher Will dictating the actual course of events in the universe. Science may not talk overtly of God, but it does accept that there is a “something else” that affects the manifested affairs of things and beings of the universe. This “something else”, scientists will agree, is beyond any deterministic laws or cause-effect relations they can postulate.

Similarly, while science does not talk of “soul”, there are many scientists who believe that not everything about a human being can be explained in terms of its material body. Of particular relevance to this discussion are the advances being made in neurosciences and artificial intelligence. It is true that modern brain imaging techniques are revolutionizing our understanding of the structure and processes of the brain and how they relate to our mental and physical functions. However, science is not anywhere close to answering a fundamental question: A human being experiences the world and is aware of its experiences. How do all the neuronal activities and processes inside the brain add up to a knowledge and vivid experience of a world outside? Neuroscientists have no answer.

Computer scientists making great strides in artificial intelligence have also no insight to offer regarding this question. Computers play games and music, predict weather, and solve mathematical problems with great speed and versatility. But when playing chess, does the computer know it is playing chess? When solving a mathematical problem does it know what problem it is solving or its significance? It does not. No computer scientist can categorically assert that computers “know” or experience anything they are doing. Robots built by future computer scientists may look and behave so very much like human beings that it may be difficult to tell them apart. But even then, the hardware and software of which robots are made, cannot vest them with the quality of knowing and experiencing. This is because knowing and experiencing are not attributes of physical matter, but of “something else”.

As Adi Sankara, the great Advaita Vedānta philosopher of the 8th Century AD, says [8]:

“asti kaścit svayaṁ nityaṁ aham pratyayalaṁbanaḥ, avasthā traya sākṣī san pañca kośa vilakṣaṇaḥ”

Something there is, which is the Absolute Entity, the Eternal Substratum for the very awareness of the Ego. It is the Witness of the three states and it is distinct from all the five sheaths.

The three states refer to the awake, dream and sleep states; the five sheaths to the physical, physiological, mental, intellectual, and sub-conscious components of the personality. That “eternal something”, asserts Sankara, is the knower of all three states yet not part of any of the five sheaths. If so, where is this witnessing knower?

According to Vedānta, it is the conscious mind which knows and experiences the world and that Consciousness is an entity distinct from the brain or any other part of the physical or mental body. This experiencer, called jīva, dwells in the body but does not die when the physical body dies. It is the jīva which can possess knowledge and not the physical body.

The Spiritual Journey: From Ignorance to Perfect Knowledge through Worldly Experiences

This brings us to a key distinction we can make between Science and Spirituality. The basic “natural sciences”, such as Physics, Chemistry and Biology, deal with matter and energy and they seek to explain all natural phenomena in terms of the known laws affecting matter and energy[2]. But matter and energy is not all there is to this universe. There is also knowledge. Vedānta postulates that the world of mind and matter is a manifestation of the three guṇas (gu-Na) or qualities of Prakṛti or Nature, namely tamas, rajas, and sattva. Matter and energy correspond to tamas, and rajas respectively, while knowledge is an entirely different guṇa corresponding to the sattva attribute of Prakṛti. For example, Science, which is a body of verified knowledge, is one manifestation of the sattva attribute. Therefore, existence of science itself disproves the materialist’s claim that everything in creation is matter and energy.

If science is focused on matter and energy, spirituality is concerned with Knowledge. One may rightly ask “Knowledge of what?” The spiritual aspirant does gain knowledge of how mind interacts with the world to produce experiences and how that mind could be disciplined and made pure enough to acquire the most sublime knowledge. Vedānta makes one of the highest statements in metaphysics when it says that the spiritual aspirant finally seeks not knowledge of anything, but Knowledge itself. That is, spirituality is ultimately concerned with knowing the “knower” and “experiencer”, the source of all Knowledge.

One of the sobering facts about science is that, while it acknowledges the world and its myriad of experiences, it cannot comprehend the purpose behind any of these. One must turn to spirituality to find the purpose of life. It is by learning the intelligent way to meet all worldly experiences that an individual gradually gains knowledge about self, just as it is by observation that scientists slowly build the edifice of science. To repeat what was stated earlier, the knowledge of importance in spirituality is not any worldly knowledge relating to matter and energy, but the knowledge of the Knower that possesses all knowledge- in other words, Knowledge of the Self. Attainment of this “Supreme Knowledge” is what is called in spiritual traditions variously as “Salvation” or “Nirvāṇa” (nir-vA-Na) or “Enlightenment”. Echoing this spiritual principle, all religions give less importance to what we experience in life, pointing out that how we meet those experiences is the key to a successful spiritual life leading to salvation. The journey to Knowledge and spiritual perfection is through the world of experiences. The purpose of our worldly life is to give us the experiences necessary to advance towards Perfection.

Spirituality As A Science

Science and spirituality, as discussed above, deal with two different aspects of reality and therefore there is no room for conflict between the two. What is more to the point is that spirituality is itself a science. The same techniques used in science, including controlled experiments and mathematical analysis, can be and have been used in understanding spirituality also[3]. We need not delve deeper into this topic here, since a bulk of this book is devoted to such a study of spirituality. When spirituality is approached thus, it takes on a definitely science-like look, capable of providing insights into our spiritual nature. Based on the work so far, there is evidence to support the view that spirituality can be studied as a distinct scientific discipline. Looking further down the road, it may become possible to teach spirituality as a science to young adults regardless of their cultural or religious background. This may be one way to cure the woes that beset the modern world due to a general lack of understanding of the true nature of spirituality and religion among both the young and older generations today.

Religion: Spiritual Food Cooked to Cultural Taste

If it is the core spiritual truths that make religions effective, is there then any real value added by the outer layers of theology and rituals? That is, do religions have any value to offer over and above what spirituality already does?

The answer is “Yes”. Religions do have a very practical value. Spirituality without religion can be too abstract and intellectual for many of us. The Upaniṣadic approach of contemplation on the Unmanifest Brahman may not be a practical choice for many since it is a hard path to follow. We have the authority of Bhagavad Gītā to back this view where the Lord explains it thus [10]:

“kleśo adhikatarasteṣāṁ avyaktāsaktacetasāṁ; avyaktā hi gatir dukhaṁ dehavadbhir avāpyate”

Greater is their trouble whose minds are set on the Unmanifested; for the goal, the Unmanifested, is very hard for the embodied to reach.

Spiritual advancement through contemplation of the Unmanifest is certainly possible for those who have learnt not to identify themselves with their own body and mind. But for the rest of us, who are “embodied”, it is hard to even conceptualize an Unmanifest Reality, let alone meditate on It. The Lord therefore goes on to suggest that, for most of us, devotion to a concrete representation of that Reality is the easier path to follow. This in fact is what religions do. The rich symbolism behind the personalities, legends and mythologies introduced by religions- the third layer in our Fig. 1.1- makes the abstract more understandable and the spiritual practices more enjoyable to everyone.

Religion, in this respect, is not unlike the food we eat. To stay healthy one must take in the necessary nutrients, the proteins, carbohydrate, vitamins etc. Now, it is certainly possible to provide these nutrients through a daily regimen of raw vegetables, grains, fruits and nuts, etc and supplemented by a handful of vitamin pills. Indeed a few well-disciplined souls may actually stick to such a Spartan diet and manage to stay healthy and happy. Future space travelers may also learn to survive on pre-packaged food designed to provide just the right amount of nutrients, but offering little by way of variety and taste. But it is far easier for most of us if the nutrients are made available in the form of an appetizing meal. That is what good cooking does. It adds flavor and appeal to the food while preserving the nutrients the body needs. Good cooks are careful not to lose nutritional value by overcooking or by adding too much fat and sugar just to make the food taste better.

In much the same way each religion has its own style of adding sugar and spices and serving spiritual truths in an appetizing way to satisfy the spiritual hunger that is in all of us. Just as many different culinary styles have evolved around the world, each capable of providing the nutrition necessary for the human body, so too many religions have developed to cater to the nutrition our spiritual body needs. The choice of food we eat is a matter of personal preference, largely determined by what we are accustomed to since childhood. As long as the method of cooking does not diminish the nutritional value of the ingredients, one cuisine is as good as another for nourishing the body. Similarly, as long as religions preserve the core spiritual values while dressing them up with the outer layers of theology, rituals etc, they will be equally efficient in providing the necessary spiritual nourishment[4]. Religion, like food, is therefore also a matter of choice largely determined by the culture in which we grow up.

In the modern “global village”, especially in cities, we see young people enjoying “ethnic” food from different parts of the world. It is dinner in a Chinese restaurant one day, lunch from an Italian carry-out stand the next day and snacking on falafel at a Middle East café yet another day. Their bodies tolerate all food equally well and are nourished equally well too. How wonderful it will be if our understanding and tolerance of religions grow to the extent that we can attend service in a church one day, pray in a mosque on the next, and worship at a temple on the following day! Indeed, the Indian mystic, Sri Ramakrishna, proved that this can be done with all due sincerity and respect towards all religions. The distinctions made today between religions are mostly superficial and not meaningful from a spiritual point of view. Like the infamous Berlin Wall, the barriers that exist between religions are artificial and unjustly divide people from people. Spirituality, on the contrary, unites us all.

In conclusion, the Vedāntic vision of spirit and matter makes it possible to more clearly understand the nature of science, spirituality and religion. We come to appreciate that each has a positive contribution to make in our lives and that they are not mutually incompatible. The material sciences, with their focus on matter and energy, bless us by making our worldly life more comfortable. Spirituality, the science of life and knowledge, blesses us individually with inner happiness and collectively with communal harmony. Religions, when practiced at their best, can serve the mankind by rendering spirituality more readily comprehensible and accessible to the average person.

[1] There are other spiritual traditions and philosophical systems around the world which are close to Vedānta. Jainism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Sufism, Taoism, and Christian Mysticism offer parallel systems of thought.

[2] Disciplines such as Psychology, Economics, Management, and Sociology must also take into account subtle mind and may be classified as “behavioral sciences”.

[3] The Maharishi University of Fairfield, Iowa has been among those in the forefront of this effort to explore and develop the scientific basis of spirituality. For a very comprehensive account of its work, the reader is referred to a recent book by Dr. Robert Boyer [9].

[4] Religions at times do tend to focus entirely on the symbolic aspects of their outer layers and lose sight of the core metaphysical spiritual truths. When this happens, it becomes a serious detriment to the credibility and effectiveness of that religion. In a now classic work, Alan Watts has very eloquently elaborated on this point in the context of the catholic Christian religion [11].